Tinnitus is typically described as the persistent ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ears without the absence of external sounds. Tinnitus is very common. It affects up to one in six adults worldwide and, for many, it can be more than a nuisance. Chronic tinnitus is associated with sleep disruption, difficulty concentrating, anxiety, stress, hormonal changes and even depression. Tinnitus is considered to be the symptom rather than the condition. This means that while there is currently no single cure available to alleviate symptoms of Tinnitus, a growing body of research shows that hearing aids can substantially reduce the burden of tinnitus, particularly when hearing loss is also present.

The Neurobiology of Tinnitus

While tinnitus is often perceived in the ears, its roots are in the brain. In most people who suffer from persistent tinnitus, some degree of sensorineural hearing loss is generally present. This hearing loss can often subtle and unrecognized. When hearing loss reduces the amount of sound reaching the brain, the auditory system does not remain passive. Instead, it adapts by increasing its sensitivity and amplifying internal neural signals in an attempt to compensate for the missing input. This process, called central gain, results in heightened spontaneous firing in the auditory cortex and dorsal cochlear nucleus (Norena & Eggermont, 2005). In simple terms, the brain begins to “turn up the volume,” but instead of hearing real sound, the person perceives an internal noise that isn’t there; a phantom sound that is the Tinnitus.

The problem goes beyond the auditory system, however. These maladaptive neural changes also engage the brain’s limbic and autonomic networks, which are the circuits that regulate emotional responses and threat detection. When these systems are recruited, tinnitus becomes not just sound but an intrusive, stress-provoking experience. This explains why some individuals report profound distress and anxiety while others with similar tinnitus loudness levels feel little emotional impact.

How Hearing Aids Work to Reduce Tinnitus

Hearing aids intervene at the source of the problem. By amplifying external sound, hearing aids help normalize activity within the auditory system. With consistent stimulation, the brain no longer needs to compensate by increasing internal gain, and spontaneous hyperactivity gradually diminishes. Neuroimaging studies suggest that auditory enrichment provided by hearing aids can support reorganization of tonotopic maps — the brain’s frequency-specific wiring — and restore more balanced neural activity (Eggermont & Roberts, 2015).

Patients often notice a simple but powerful effect: when the world of sound becomes richer, the contrast between tinnitus and silence fades. The buzzing or ringing no longer stands out against a background of environmental sound. Over time, this decreased salience helps quiet the limbic system and stress response, making tinnitus less intrusive and emotionally taxing.

The Strength of the Clinical Evidence

The benefits of hearing aids for tinnitus are not just theoretical; they are consistently supported by clinical research and anecdotal reports. Decades of observational studies and controlled trials have demonstrated meaningful improvements in both tinnitus perception and tinnitus-related distress among hearing aid users.

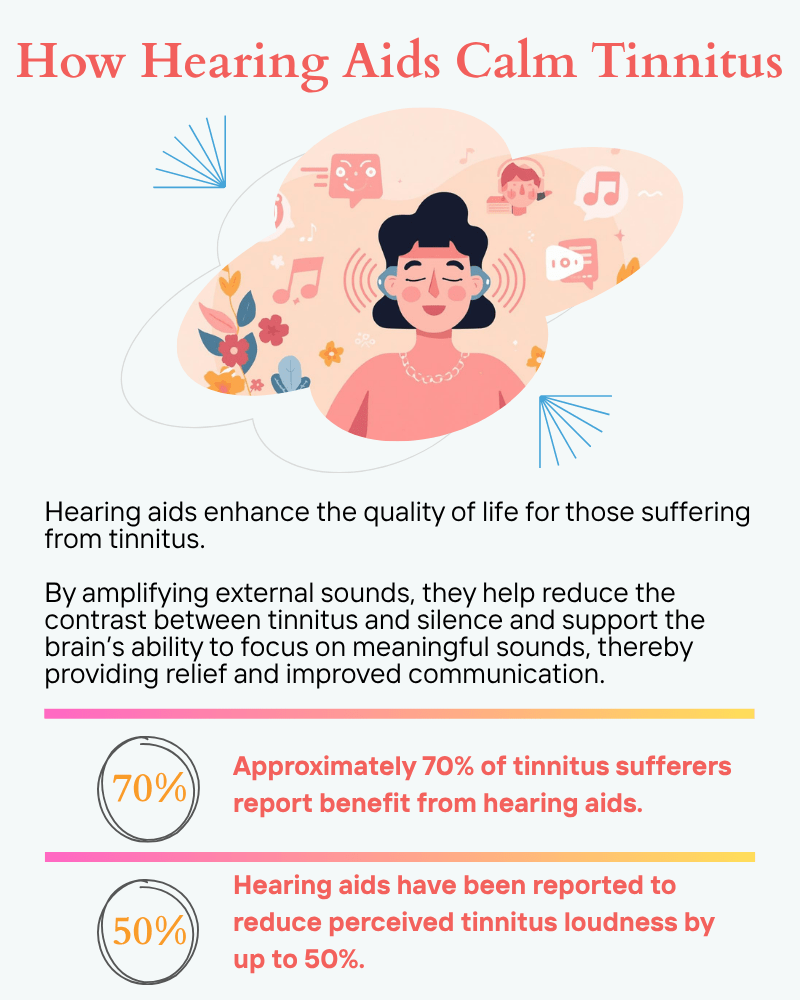

One of the earliest and most cited findings comes from long-term clinical follow-ups showing that between 60% and 70% of patients reported noticeable tinnitus relief once appropriately fitted with hearing aids(Searchfield et al., 2010). These improvements are not limited to loudness reduction; many patients report a shift in how bothersome their tinnitus feels, with improvements in concentration, sleep, and emotional well-being.

A systematic review by Sereda and colleagues, published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in 2018, further supports the role of amplification. The review concluded that, for patients with hearing loss, amplification can provide significant benefit in reducing the impact of tinnitus. Notably, the evidence suggests that improvement is not solely due to masking of the tinnitus by the hearing aids; rather, it reflects genuine neuroplastic adaptation when the auditory system is re-engaged.

Modern hearing technology has refined these outcomes even further. Current modern digital hearing aids allow precise programming tailored to a patient’s specific hearing profile and tinnitus pitch. Many devices now incorporate dedicated tinnitus management features, such as sound habituation programs, sound enrichment or integrated noise generators, which can provide additional relief for patients with severe distress. When combined with patient education and counseling, outcomes are even stronger, as patients learn to reframe their response to the sound while benefiting from the neurophysiological effects of amplification.

A Practical, Evidence-Based First Step

Because tinnitus so often coexists with hearing loss, a comprehensive audiological evaluation and hearing aid fitting is an important and evidence-based first step in management. Amplification directly targets the mechanism driving tinnitus by restoring sound, stabilizing the auditory system, and reducing the brain’s need to generate phantom noise. Hearing aids are also safe, non-invasive, and can be integrated with additional therapies when necessary.

While no single intervention can eliminate tinnitus in all cases, the consistent body of research shows that hearing aids provide real and measurable relief for many. They improve communication, reduce listening effort, and — just as importantly — calm the neural and emotional pathways that make tinnitus distressing.

The Bottom Line

Tinnitus is not simply a mysterious ringing in the ears. It is the brain’s reaction to reduced hearing input, coupled with an emotional response that can amplify suffering. By restoring access to sound and reshaping maladaptive brain activity, hearing aids can help patients move from distress to control and reclaim a sense of quiet in their daily lives.

References

Norena AJ, Eggermont JJ. Changes in spontaneous neural activity immediately after an acoustic trauma: implications for neural correlates of tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2005;26(2):239–253.

Eggermont JJ, Roberts LE. Tinnitus: animal models and findings in humans. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;361(1):311–336.

Searchfield GD, Kaur M, Martin WH. Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: Tinnitus management. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21(7):461–473.

Sereda M, Xia J, El Refaie A, Hall DA, Hoare DJ. Sound therapy (using amplification devices and/or sound generators) for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD013094.

Book your hearing evaluation

Or fill out the form below and our audiology team can call you to arrange a convenient time for your evaluation.

Recent posts

October 4, 2025

Your Ears Never Sleep

May 1, 2025

Concussion and Hearing: The Hidden Impact

.jpg)